|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Rising Sea Levels

The Flooding of the Century?

In the last 50 years the sea level has risen less than 20 cm (6 inches). No big deal right? That 10 cm rise is the result of slow glacial melt, snow and ice from mountains world wide melting plus chunks of arctic and antarctic ice which have melted into the sea. The problem is that the average temperature in the antarctic has been slowly rising and it used to be a rare occasion when antartic temperatures rose above 0 Celcius. The highest temperature ever recorded at an antarctic science station was January 5th 1974 when it hit 15 C (59 F) during the height of summer (like Australia, the Antarctic's seasons are reversed). In recent years however scientists have been recording unusually warm weather in the antarctic. Still below freezing, but the average temperature has been rising and scientists have been recording a greater number of days which the temperature rises above freezing. Most scientists agree that global warming presents the greatest threat to the environment. There is little doubt that the Earth is heating up. In the last century the average temperature has climbed about 0.6 degrees Celsius (about 1 degree Fahrenheit) around the world. No big deal right? The problem is the dispersion of that extra heat. The temperatures around the equator have stayed relatively the same, but it is the temperatures in arctic regions that have seen the most changes, often rising 5 to 10 degrees Celcius above normal. The problem is that the extra 5 degrees can make the difference between -3 Celcius and +2 Celcius. From the melting of the ice cap on Mount Kilimanjaro, Africa's tallest peak, to the melting of arctic and antarctic ice the results are becoming clear. The biggest danger many scientists warn is that global warming will cause sea levels to rise dramatically. Thermal expansion has already raised the sea level an estimated 10 centimeters. But that's nothing compared to what would happen when Greenland's massive ice sheet melts. "The consequences would be catastrophic," said Jonathan Overpeck, director of the Institute for the Study of Planet Earth at the University of Arizona in Tucson. "Even with a small sea level rise, we're going to destroy whole nations and their cultures that have existed for thousands of years."

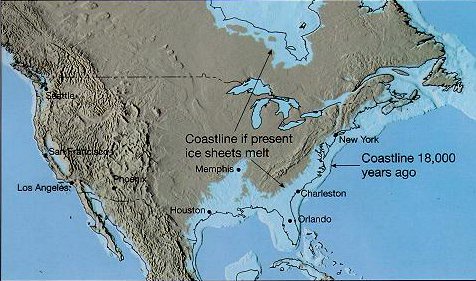

Overpeck and his colleagues have used computer models to create a series of maps that show how susceptible coastal cities and island countries are to the sea rising at different levels. The maps show that a mere 1-meter (3-foot) rise would swamp cities all along the American eastern seaboard. A 6-meter (20-foot) sea level rise would submerge a large part of Florida.

UnderwaterGlaciers and sea ice in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres are already melting at a rapid pace, placing animals like polar bears at risk because they are dependent upon sea ice. "The real question is what's going to happen to Greenland and Antarctica," Stouffer said. "That's where the bulk of all the fresh water is tied up." A recent study suggested that Greenland's ice sheet will begin to melt if the temperature there rises by 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit). Something which could happen in the next 20 years as warmer air currents push farther north. The complete melting of Greenland would raise sea levels by 7 meters (23 feet). Even a partial melting would have a devastating impact on low-lying island countries, such as the Indian Ocean's Maldives, Florida and many coastal cities, which would be entirely or partially submerged. Densely populated areas like the Nile Delta and parts of Bangladesh would become uninhabitable, potentially driving hundreds of millions of people from their land. A one-meter sea level rise would wreak particular havoc on the Gulf Coast and eastern seaboard of the United States. "No one will be free from this," said Overpeck, whose maps show that every U.S. East Coast city from Boston to Miami would be swamped. A one-meter sea rise in New Orleans, Overpeck said, would mean "no more Mardi Gras." Hurricane Katrina would feel like a mere taste of what was to come.

Future GenerationsMost climate scientists agree that global warming is a threat that has gone unchecked for too long. "Is society aware of the seriousness of climate warming? I don't think so," said Marianne Douglas, a geology professor at the University of Toronto. "If we were, we'd all be leading our lives differently. We'd see a society that embraced alternative sources of energy, with less dependency on fossil fuels." Overpeck says passing on the problem of global warming to future generations is like ignoring a government budget deficit. "Except with the deficit, there are economic mechanisms that could be put in place to get out of the large deficit," he said. "With sea level rise, there's really no technological way to put the ice back on Greenland." "We did not expect that the ice sheets can react to warming on such a short time scale," said Konrad Steffen, a geographer at the University of Colorado at Boulder who has spent the past 15 years monitoring ice sheets in Greenland (map). Scientists thought ice sheets and glaciers would respond to warming slowly over hundreds of years. The current acceleration could be a short-term adjustment to the warmer temperatures, Steffen said. "Something dramatic is happening," said Göran Ekström, a seismologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Ekström and colleagues report that glacial earthquakes—seaward lurches of glaciers—in Greenland have more than doubled in number since 2002. Most of the glacial earthquakes occur in July and August, at the height of the Northern Hemisphere's summer melt. The finding complements a study that found some of Greenland's glaciers have doubled in speed over the past five years, said Jay Zwally, a glaciologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Ancient FloodingAbout 130,000 years ago, global sea levels were 13 to 20 feet (4 to 6 meters) higher than they are today. Scientists have determined this by studying ancient coral reefs that now sit high and dry, and other so-called paleo-climate clues. The University of Arizona's Overpeck and his colleagues wanted to understand what sort of climate conditions were necessary to create such high sea levels. Scientists believe that Earth's orbit had shifted slightly at the time, giving the Northern Hemisphere greater exposure to the sun. When Overpeck's team plugged those orbital conditions into a computer model, they found the Arctic warmed 5º to 8ºF (3º to 5ºC), sufficient to melt enough Arctic ice to explain the sea level rise. But the researchers also know how much the Greenland ice sheet, which holds most of the Arctic water, melted at the time. When they plug that data into the model, the melt only accounts for 7.2 to 11.2 feet (2.2 to 3.4 meters) of the water rise. But unlike 130,000 years ago, today's atmospheric warming is global and less localized.

Can We Fix It?According to NASA glaciologist Zwally humans can limit the effects of global warming by acting now to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases. But if we continue to pollute at the current pace, he says, the Greenland ice sheet and part of Antarctica could be undergoing irreversible decline. "Man is doing an experiment with the ice sheets, which is a scientifically interesting experiment, except it is going to have some serious consequences," he said. "And the longer we wait to do something about climate warming, the more serious it's going to be."

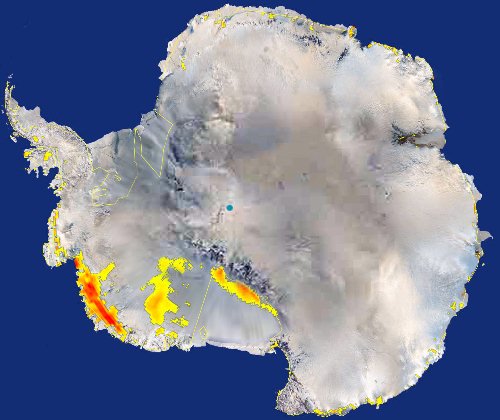

The Antarctic DebateThe Antarctica holds 90 percent of the world's ice and is one of the biggest puzzles in the debate on global warming with risks that any thaw could raise sea levels faster than any projections. Even if a fraction melted, Antarctica could damage nations from Bangladesh to Tuvalu in the Pacific and cities from Shanghai to New York. It has enough ice to raise sea levels by 57 metres if it melted, over thousands of years. "Most people looking at it are thinking more in terms of a metre," said John Moore of the Arctic Centre at the University of Lapland. "Insurance companies don't know to a factor of 100 where to set their insurance premiums for coastal areas in Florida." Some island nations, such as the Maldives in the Indian Ocean, are building defences costing millions of dollars and want to know how high to build. "I think it will be...certainly at the high end of the range," said Kim Holmen, research director of the Norwegian Polar Institute, at the Troll Station 250 km from the coast in Antarctica. Set amid jagged mountains like the mythical homes of troll giants, this part of east Antarctica is the world's deep freeze with no sign of a thaw. Temperatures were about minus 15 Celsius at the height of the Antarctic summer. "It's my view that more than a metre of sea-level rise can't be ruled out," said Stefan Rahmstorf, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany. He said many experts "think the IPCC range is unfortunately not the full story". Even so, most experts said it is still impossible to model how the ice will react. Antarctica may accumulate more ice this century because of warming, blamed by the IPCC mainly on human use of fossil fuels, rather than slide faster into the sea. "The crux of this problem is that we are moving into an era where we are observing changes in the climate system that have never before been seen in human history," said Gerald Meehl, of the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research. "Ice sheets fall into that category. Quite simply, at this time we don't have a good upper-range estimate of 'how much sea- level rise and how fast'," he said. Meehl, a coordinating lead author of the IPCC report, said that gave the best view. The core prediction for sea-level rise by the IPCC, which shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with former U.S. Vice President Al Gore, is for a gain of 18 to 59 cms in the coming century, after 17 cms during this past century.

The forecast rate includes faster ice flow from Antarctica and Greenland observed from 1993-2003 but the IPCC said this could increase or decrease in future. If the flow grows in line with temperature rises, it would add a further 10 to 20 cms. "The IPCC range only takes into account things that can be modelled," said Jonathan Gregory of the University of Reading, who was also among authors who stuck by the conclusions. "There are lots and lots of reasons why you can say there will be large changes. But you can't say it without more evidence," he said. Among worrying scenarios is the chance Antarctica will slide faster into the sea, perhaps if a ring of sea ice melts away in warmer oceans. Or melt water might flow under the ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland, and act a lubricant to speed a slide. "In the long term we are in trouble...Greenland is close to a 'tipping point'," or an irreversible meltdown that would last hundreds of years, Huybrechts said. Greenland has enough ice to raise world sea levels by 7 metres if it all vanished. One IPCC author said the uncertainties are stacking up towards rising seas. "I firmly believe sea-level estimates are conservative," said Andrew Weaver of the University of Victoria, Canada.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Website Design + SEO by designSEO.ca ~ Owned + Edited by Suzanne MacNevin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||